Sharing cultural heritage on Eid-ul-Fitr through food

A Pakistani-Afghan mother shares the dish of her childhood with her Canadian-born son.

As we approach the end of Ramadan, lunar sighting arguments notwithstanding, I begin to prepare for Eid-ul-Fitr in my Toronto home, in the same way the women in my family always did before me. First, I make sure to stock up on 2 litres of full-fat milk and 1 litre of full cream. Then, I check my pantry for cardamom pods, ghee, sugar, slivered almonds and tart green sultanas, dried rose buds, edible silver leaf, and the most important ingredient of all — a package of roasted vermicelli. The pot goes on the stove, dollops of ghee are added by the spoonful, crushed cardamom seeds go in, and a heady, warm scent begins to fill our Toronto home — a scent which tethers me to my mother and her kitchen, and all the Eids I've spent with my parents and sisters, wearing perfectly ironed silk kurta shalwars, golden chappals, and neon-coloured glass bangles sent by my grandmother in Pakistan.

Given the precision of astronomical movements, the new moon is foretold. And yet, every year, Muslims around the world rely on the sighting of a slender crescent moon suspended in the sky to confirm the festival of Eid-ul-Fitr, marking the end of Ramadan, the Islamic holy month of fasting. The date for Eid can vary by a day or two, due to different stances within the Muslim community, as to whether the lunar sighting counts: when seen with the naked eye, or using mathematical calculations.

Eid is a time for decadent eating after a month of self-restraint. In our family, the morning after we offer our Eid prayers, we start with a bowlful of Shir Khurma, a dish which takes me back to the city of my birth, Lahore. In my ancestral home in Lahore, on Eid-ul-Fitr our table is laid out with a guava and mango salad, laced with lime, red chili and salt; soft, finger-thin chicken and sliced cucumber sandwiches; and orbs of fudge-like confections, called burfi. Jasmine tea is served in my grandmother's red, Russian Gardner porcelain cups, which her mother-in-law brought back from Afghanistan in the late 1800s. In the centre of the table sits a large bowl of Shir Khurma, a milky, creamy, matrilineal recipe which has been passed down through an oral tradition from generation to generation.

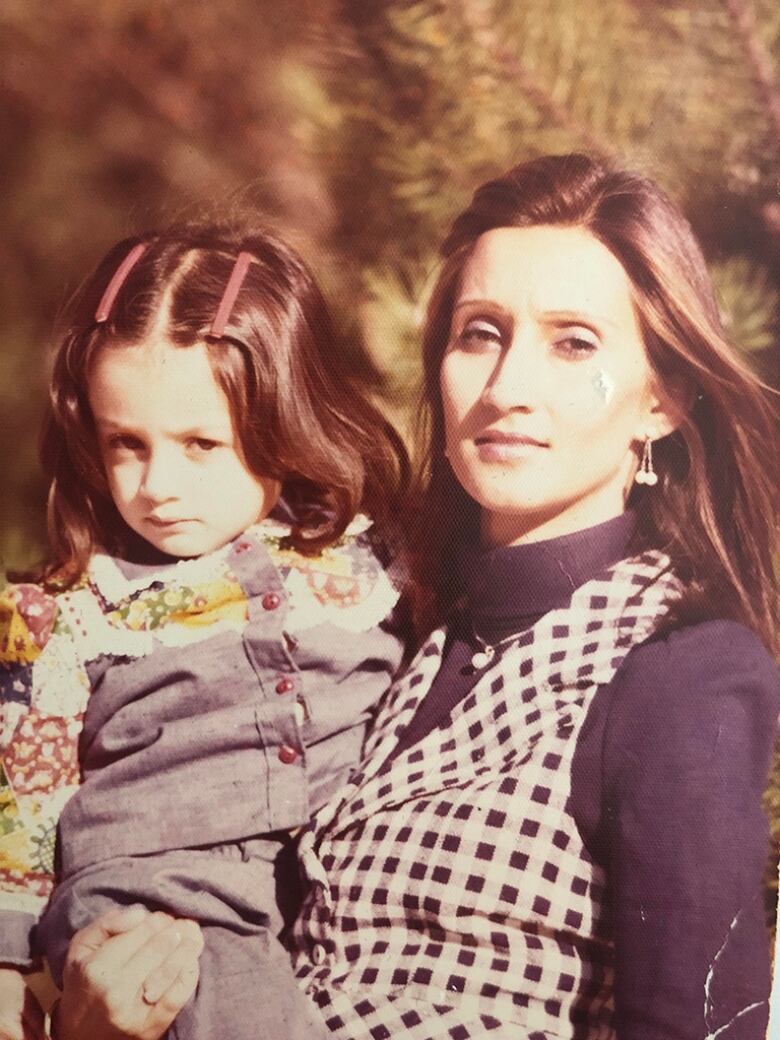

As I prepare this dish in my kitchen in Toronto, I wonder if my son, who is almost six-years-old, will ever make this recipe which links him to the stories of his mother's Pakistani-Afghan heritage. I want my son to grow up hearing and knowing these stories — the stories of his mother. His mother's mother.

I fear these stories will be lost, as they cross generations and borders.

My son was born in Toronto at St. Mike's Hospital, in a Toronto summer, when Ontario peaches are their ripest. Every morning, he checks the NHL scores (I've been supporting his team, the Pittsburgh Penguins, too — Go, Crosby!). When he comes home from school, he finishes a bowl of steamed basmati rice, with cucumber raita and a saffron-laced chicken and tomato curry. Zain, my husband, and I speak to him in Urdu, but the response is always in English, and these days, in French. A parent who lives between binary worlds — the East — the countries of my heritage, Pakistan, Afghanistan and Iran — and the West — Toronto, I wonder if everything I have learned from my parents, the poems of Ghalib and Bulleh Shah, the honorifics for our elders — everyone is an 'Aunty' or an 'Uncle', elder sister is Apa, and elder brother, Bhai — will be lost and forgotten as my son grows up in the West.

Here, in Toronto, a place I call home after almost a decade, the Eid rituals have been somewhat different without any close family near us. There have been no silk kurta shalwars to iron, no glass bangles to wear. Our Eids have been quiet over the past few years, and that sense of homesickness for Pakistan always bubbles up as this holiday approaches. But as my son grows older, I want to create an environment in which he, too, will feel tethered to his mother through the scents and smells of her kitchen on a festive day.

I left my mother's home for a job in the United Nations in Rome, Italy, in 2003. The one tradition I have carried on for almost fifteen years — first in Rome, and now in Toronto — is the ritual of making my mother's Shir Khurma for Eid. Every year, I stand over the pot for over an hour, gently stirring the sugar, milk and cream, till it starts to thicken, and smell like toffee. Sometimes, I add a vermillion Persian saffron to the pot. Poured into jam jars, and dusted with rose petals and crushed pistachios, I have taken it to the office, to gift to my colleagues. Most recently, I have shared a bowlful of it, a few days before Eid, with my dear Sikh-Canadian friend and her family, over a Kashmiri-style dinner which her mother prepared for us.

And on Eid this year, just as my parents always did every year during my childhood, I will open up my home to my Canadian friends, the ones who don't celebrate Eid, so that our son can see that Eid is about community, about sharing bowls of Shir Khurma (you can find my recipe, pictured at the top of this story, here), adorned with a sliver of silver leaf, and standing around the kitchen counter together, chatting and laughing, whilst eating hot, greasy, crispy potato pakoras, alongside bowls of tamarind-doused chickpea, tomato, and shallot chaat.

Shayma Owaise Saadat is a Food Writer and Chef. She lives in Toronto with her husband and son. You can follow her culinary journey at www.ShaymaSaadat.com or on Instagram.