The haunted, homophobic history of Toronto is a real-life horror story

The violence follows a formula as reliable as any slasher movie, and David Demchuk's Red X puts it on the page

Shelfies is a column by writer Alicia Elliott that looks at arts and culture through the prism of the books on her shelf.

Every October, I commit myself to watching a month of horror movies. This year, I've been going through some of the most (in)famous slasher series: Friday the 13th, A Nightmare on Elm Street and Halloween.

What's most striking about watching these series in order and in close succession is the relentlessness of their villains. Jason Voorhees, Freddie Krueger and Michael Myers simply cannot be stopped — not by burning, stabbing, dismembering, beating, not even by death. There is a sense that the ending of each movie is simply the ending of a chapter, and all one needs to do is turn the page — or put on the next movie, as it were — to see Jason, Freddie or Michael awaken and start their deluge of terror on unsuspecting teenagers once more. These slashing sprees are a sort of Groundhog Day of murders, each movie following generally the same structure, with the only real changes being the actors playing their victims and, sometimes, the methods of killing.

It reminds me of the haunted, homophobic history of Canada — a tapestry of terror where, like a slasher series, the horror never completely stops, but merely cycles through again and again, taking more and more victims each time. The difference is that, unlike horror villains who remain consistent and identifiable, the insidiousness of homophobia and transphobia is that it can shapeshift, moving from person to person and institution to institution, leaving a trail of pain and loss that has no beginning or end. Whether it manifests in individual acts like hate crimes committed against queer and trans folks (which are on the rise in Canada) or systemic acts like the Canadian police chiefs opposing the decriminalization of homosexuality in 1968 (which they only apologized for in late 2020), homophobia and transphobia continue to be ever-present, making everyday life dangerous for LGBTQ2+ folks.

When the world around you is, in many ways, telling you that you deserve violence and hate simply for being yourself, how can you battle that idea alone? How can you help but internalize it, the horrors infiltrating your mind until you can't even escape it in your thoughts? How can you ever feel safe?

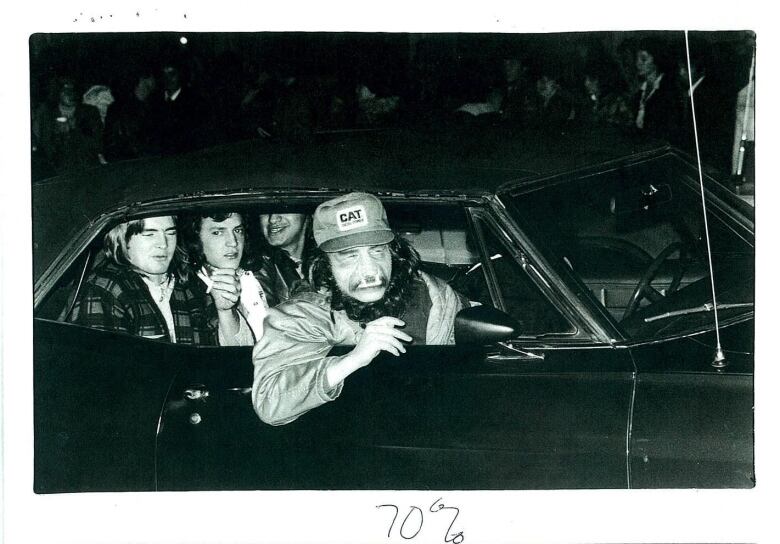

This is the LGBTQ2+ history of Canada. I would consider this history a horror story. Evidently, so would David Demchuk. His latest novel, Red X, traces that haunted history in Toronto: the controversial story of "gay pioneer" Alexander Wood, who arrived in Upper Canada in 1793 and was eventually outcast back to Scotland following an 1810 sex scandal; the AIDS epidemic; the 1981 and 2000 bathhouse raids; the beatings at Cherry Beach that gay and street-involved folks said they endured at the hands of Toronto police officers; the harassment of drag ball attendees like Michelle DuBarry every Halloween for years; and the targeting of gay men of colour by a serial killer in Toronto's Gay Village.

Each piece of this history is sprinkled through Red X. Indeed, in Demchuk's novel, every eight years, more and more gay men disappear, leaving behind friends and family who are helpless to find them. This reflects the reality of being a gay man in Toronto at any time in the past 50 years. Demchuk himself knew one of the men who was murdered by the serial killer whose name and "sunny, smiling face" we all now know. And yet, in another incidence of history repeating itself, between 1975-1978, there were 14 gay men brutally murdered in the city. Half of those cases remain unsolved. They cannot all have been committed by one person.

When the world around you is, in many ways, telling you that you deserve violence and hate simply for being yourself, how can you battle that idea alone? How can you ever feel safe?- Alicia Elliott

In Megan Pillow's Electric Literature essay, "Horror Lives in the Body," she describes the way that horrific moments live on in our bodies as almost an echo, so that each time we see horror happening onscreen, we are forced to remember our bodies are "a living archive of human trauma, a collection of bodily and psychological horrors, the things that we can often see coming but ultimately cannot escape." When I read Red X, I could not help but think of the horrors of homophobia and transphobia — horrors that have manifested themselves "in a collection of bodily and psychological horrors" in the lives of every single character in the book. These are horrors they know are coming, can see coming as clearly as Crystal Lake campers can see Jason coming, but are still unable to escape.

Worse, I could not help but think of the third season of CBC's Uncover podcast, hosted by Justin Ling, which focused on the murders in Toronto's Gay Village. In one episode, trans activist Nicki Ward tells Ling about how, when the Toronto Police finally had a meeting with the LGBTQ2+ community, the police asked how many of them had been assaulted before — and people started to laugh. Not only had they all been assaulted in the past, Ward said, they'd all been assaulted in the recent past. Violence was a language they knew well. Hatred not only left scars on their bodies; it built up inside them like calcium deposits, holding the horrors of homophobia and transphobia in their very marrow until it turned them against themselves. There was no place that was safe. (As a bisexual woman who grew up Catholic, hating other queer people as well as the parts of myself that were attracted to women for years, I can relate.)

In the nonfiction essays that break up each section of his novel, Demchuk talks about the ways that violence and homophobia combine to create not only a vacuum for positive queer representation, but also a deep-rooted self-hatred. In one such essay, he goes through the interconnected history of queerness and horror — the catch-22 of queerness being constantly villainized in horror, but horror also being the only genre and space where queerness could be explored or even represented until recently. For example, while the disavowal of villainous transgender or cross-dressing characters such as Norman Bates in Psycho and Buffalo Bill in The Silence of the Lambs have been fairly unanimous, there are also trans folks who want to reclaim trans horror villains like Angela Baker in Sleepaway Camp. Horror movies like The Babadook, on the other hand — where the monster quite literally comes out of the closet, and cannot be killed, only fed and lived with — offer the opportunity for queer people to read queerness as the film's central metaphor. As Demchuk points out, every horror story that has featured a "secret past," "debilitating disease," "duplicitous nature" or "unbridled hedonism" could be "a carefully coded example of queer horror."

Sometimes, in a society that doesn't offer positive representation, being seen as a villain could be better than being not seen at all. Indeed, Demchuk writes, "for queer readers, hatred and self-hatred were the stinging medicines we were forced to consume if we were to satisfy our need to see ourselves." Naturally, this makes working in the genre a complex task for Demchuk: "I continually have to question whether I am demonizing sides of myself that I should be celebrating and embracing."

This, ultimately, is the true horror of Red X: the way that nonfiction becomes fiction and fiction becomes nonfiction, interrupting one another and blending together until you can no longer tell what is real and what is not. After all, aren't homophobia and transphobia — and the hatred that spurs them and their violence on — real, always? Don't they, like Jason, Freddie, Michael, and Red X's Nicholas, come in the form of seemingly unstoppable, undefeatable forces that will keep taking victims over and over until we somehow figure out how to make them stop?

"Imagine that something is attacking your family, your friends, your community. Imagine that something is attacking you," Demchuk writes. "What if it's invisible, in the air, all around you, on the street, in the club, at the bar... in your bed, inside your body, your lungs, your heart, your mouth... what do you do?"

You keep fighting, Demchuk argues, because you have no other choice: "fighting with your heartbeat even when you dream... the fight doesn't end until you do. And then, if you're extremely lucky, there are people who love you who bury you... their hearts keep fighting in your wake, carrying your fight forward."

In the face of near-constant horrors — horrors that live on inside of us — we must continue to carry that fight forward, always. For Abdulbasir Faizat, Skandaraj Navaratnam, Majeed Kayhan, Soroush Mahmudi, Dean Lisowick, Silim Esen, Kirushna Kumar Kanagaratnam, Andrew Kinsman, Tess Richey, Alloura Wells, Cassandro Do. For those who have come before, and those who will come after. For a future where our bodies and minds can, one day, maybe, be free.