25 years ago, Miss Saigon gave me my big break; 25 years later, would I be protesting it?

Filmmaker and musician Romeo Candido reflects on Miss Saigon in the age of #representationmatters

Twenty-five years! It's been 25 years since I made my professional debut in the (then) mega-musical Miss Saigon — the "modern" retelling of Madama Butterfly — where a Vietnamese prostitute with a voice of gold falls in love with an American G.I. on the eve of the fall of Saigon. Spoiler alert, things end on a minor chord.

This Saturday, the cast and crew are having an anniversary reunion at the same theatre where we premiered our show so long ago, and on the eve of the event, this one time chorus member has done some reflecting. In 2018, would I still feel right telling this Vietnamese story as a Filipino?

Miss Saigon gave me the permission to dream big.

Back in the early '90s, Miss Saigon was a major cultural milestone. Famous actor Jonathan Pryce originated the role in London and on Broadway (in yellow face). It featured the most technologically advanced theatrical centrepiece of the time (a helicopter). And it introduced audiences to major international talent (Lea Salonga).

For me, it was the first time that I saw Filipinos become known for being the karaoke singers that we were. Due to our colonized past, we adopted western music early on and have been singing it ever since. We were perfect to cast as Miss Saigon's Vietnamese. Southeast Asian genetics but fed on a diet of Broadway show tunes and ballads.

I was a first year theatre student failing out of York University when I auditioned for the role. The open call took place at the Roy Thomson Hall. It was the biggest "cattle call" in Toronto's theatre history with more than 2,000 people showing up with Broadway dreams and Les Miz sheet music. The audition itself was a news story because the thousands of hopefuls would eventually be whittled down to 32 performers who'd open a brand new theatre, the Princess Of Wales — named after the late Princess Diana, and Toronto's first privately built theatre in 50 years.

After eight callbacks, one rejection and one re-invite to audition because someone dropped out, I miraculously made it into the original cast of Miss Saigon. This was a big effing deal for all the Asian cast members. It was the equivalent to being drafted in the NHL and winning American Idol at the same time, and as part of the show I had top notch-training. We had a West End director, Broadway choreographers and Alain Boublil and Claude-Michel Schönberg (the lyricist and composer, and also the musical minds behind Les Miserables). They were all present to help mould a cast of inexperienced Asian Canadian performers into real professionals with cast jackets and everything. I felt like I was part of an elite club of musical theatre artists that was no longer just for white people.

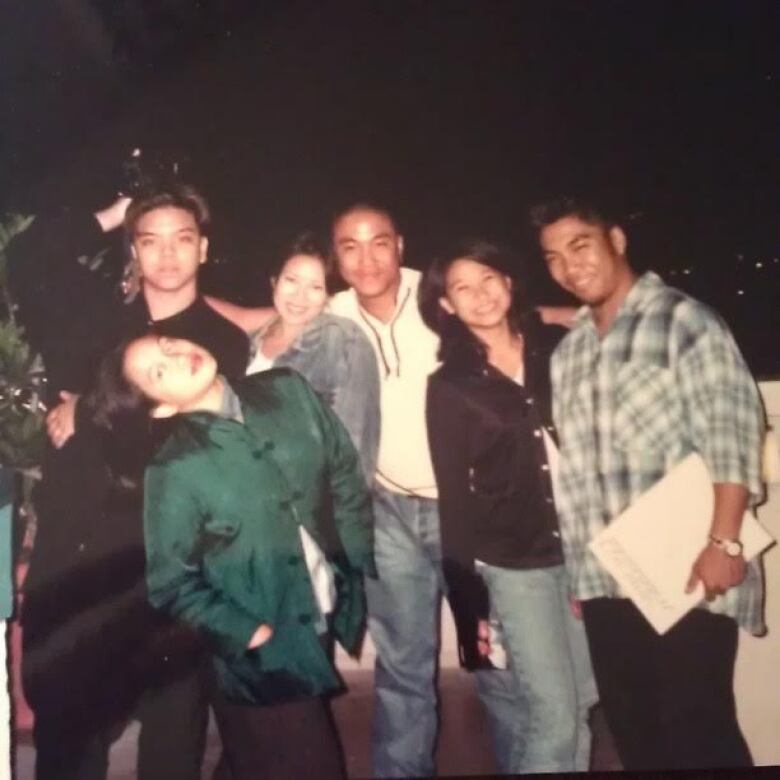

My ambition to be a filmmaker began when I bought my first camera with my Saigon money. This was my first doc, the opening night party of our show.

Before Miss Saigon, it was slim pickings for Asian performers. The only opportunities were a mix of community theatre, karaoke nights and cultural events. "Always as a hobby, never as a career" was the unofficial tagline for Asian parents everywhere.

Miss Saigon was the only show that had a predominantly Asian cast at the time. It gave us that validation and that that initial push, without which, many of us wouldn't have pursued a life in the arts.

A lot of my chosen family comes from that group. Much of my professional habits came from there. And it instilled in me that naïve but relentless belief that I can accomplish anything I put my heart into. For that, and for all of its blessings, I'm forever grateful. Twenty-five years ago Miss Saigon gave me the permission to dream big.

Meanwhile, outside the theatre, there were activists protesting the show's portrayal of Asian women as prostitutes, and its whitewashing of Vietnamese history. I would have debates with them outside the theatre. They would question why I was perpetuating these negative Asian stereotypes. My defense was that we did research (we watched a PBS doc) and were trying to be truthful to the stories of the Vietnamese. But internally, I knew it was simply because no one else was gonna pay me for pursuing my dreams. In retrospect, that really wasn't enough.

Twenty-five years later, would I be the one protesting outside the show on opening night?

I have not done professional theatre as a performer since. After Miss Saigon there were so few opportunities in the city for Asian chorus boys like me that I was forced to figure out something else. It was a rude awakening for sure. So began my journey of creating my own opportunities.

I turned to my own culture as the source of inspiration, and I continue to draw from it. My resumé is stacked with Filipino-centric projects: feature films, TV shows, docs, music projects (DATU) and a musical I created with Carmen DeJesus, another Miss Saigon alum, called Prison Dancer:The Musical.

In my journey to tell my "authentic" story, it became apparent that when other people tried to do it, they would do the Filipino experience a disservice. I not only became friends with the activists who were protesting outside the Princess of Wales Theatre 25 years ago, but I have since been mentored by them and have collaborated with them in shining a light on our people and that which has both oppressed and lifts us.

As I am about to be reunited with many loved ones from back in my Miss Saigon days, I ask myself if I would still feel right doing a show, written by white men, directed by white men, telling the story of the Asian experience. Twenty-five years later, do I find the white saviour story at the heart of the musical romantic or problematic? Twenty-five years later, could I justify playing a one-dimensional Vietcong soldier and a Japanese sex tourist for the sake of a paycheque? Twenty-five years later, would I be the one protesting outside the show on opening night?

The show means the world to me. But in this age of #representationmatters, it is just not good enough for the people on stage to be diverse. It is just not good enough to hear generic Asian-flavoured western music pass for the music of a people and region. It is just not good enough for the story of a culturally specific group be told, composed, created and performed by people who are not of that culture.

Miss Saigon gave me my start as an artist, but what matters for me the most is that the stories we tell, the songs we sing, the dances we dance come from our own culture — that they push our own traditions forward.

Personally, I think it's time to retire Miss Saigon so we can make room for that next show that will launch that next generation of Asian performers, because after all this time, if this show continues to be the bar for musicals with a predominantly Asian cast, then we are still just doing karaoke.