The inventor who tried to make a one-handed keyboard

University student's design meant each key typed two letters

Computers were getting smaller in 1991, and it was getting harder to type on the tiny keyboards that came with them.

That gave 21-year-old Edgar Matias an idea.

"While the pocket computers are cute and functional, they're too small for the touch typist," explained reporter Howard Green in a profile for the CBC business program Venture on Feb. 10, 1991. "Two hands just won't fit the real estate."

Matias said he was sitting in English class, "staring off into the distance," when it struck him.

One key, two letters

"I thought of assigning two letters to a key," said Matias.

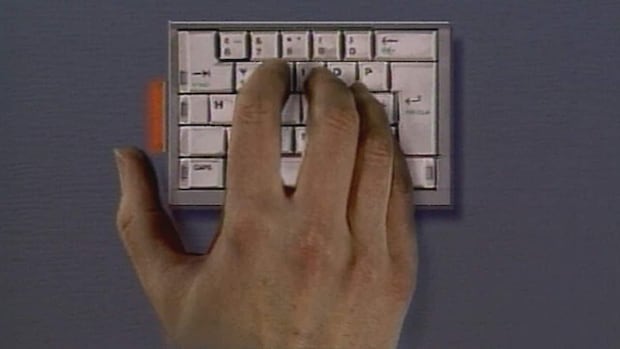

In effect, a conventional keyboard was split in half, then one half was placed under the other, said Green, as a visualization played on screen.

"This way, the touch typist can use similar moves, but with just one hand. A simple Option key allows for the switching," said the reporter.

Matias said he didn't want to be overly confident, but he didn't see how it could fail.

A 1-in-50 chance of success

By continuing to attend school, Matias had the ear of a mentor — Professor Bill Buxton, who, Green said, consulted "in California's Silicon Valley."

Together they were testing Matias's idea with a computer program because he hadn't yet produced a working prototype.

"Used as an electronic notepad, it has to allow the user to beat the speed of handwriting," said Green.

Buxton showed three other one-handed keyboards in his collection, none of which had succeeded.

But, Green said, Buxton had agreed to "fund and oversee" a test of Matias's innovation. But he still only gave it "a one in 50 chance of success," said Green.

"I'm a dreamer," said Buxton, explaining why he supported an invention that seemed to him more likely to fail than succeed. "Just because the status quo has this inertia doesn't mean it's right."